I returned to the classroom as a student after an absence of twenty years. What I’d loved about being a lit student came back in a rush. The one-credit course that met one hour, once a week was called a slow read – a genre of course design that I can’t recommend more highly.

A slow read is just what it sounds like: an entire fifteen-week semester devoted to one text. In this case, it was Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy.

Ah, Tristram.

This was a book I knew both well and not at all, having tried and failed to read it a few times while pursuing a doctorate in English, another trial which I also failed.

Reading it successfully as a full-time worker and mother-of-two (aka a grown-ass woman), led by a professor who’d taught it many times was, in a word, rapturous.

I wasn’t reading it for anything other than for pleasure…and for what I could learn as a fiction writer.

One teachable moment in Tristram Shandy has stayed with me.

Susannah descends a staircase with a candle.

At the top, she is of one mind.

At the bottom, another.

Poof.

Sterne uses his signature form of slapstick comedy to illustrate the mind’s associative quality, its tendency to hop from one idea to another using segues as stones across a steam. (Locke’s Essay Concerning Human Understanding, made light.)

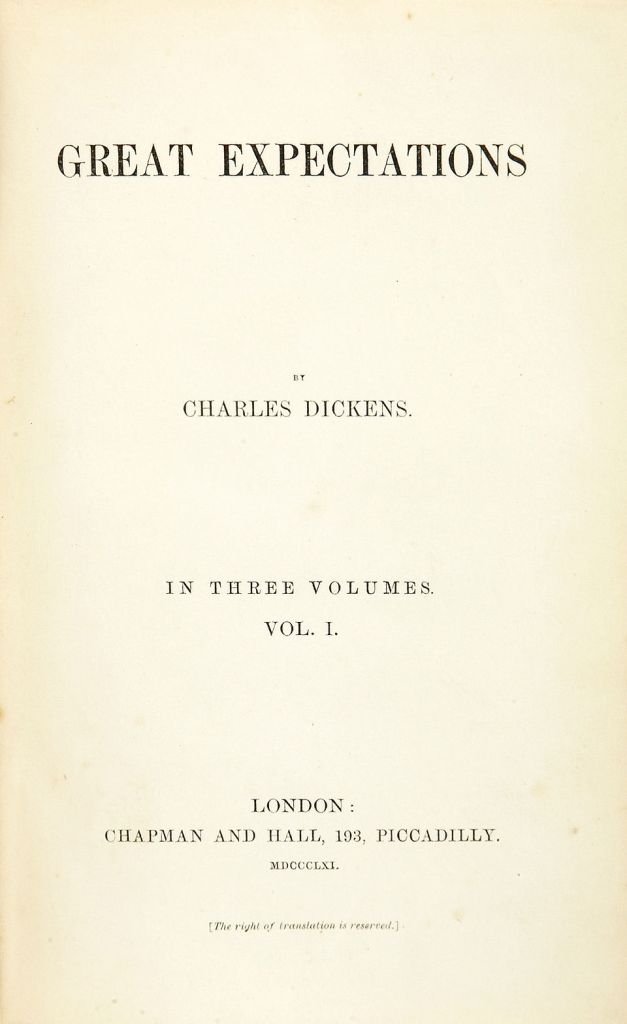

I found a scene in Great Expectations this week that reminded me that when a character’s mind changes, it needn’t be a game of interiority.

A reader can be shown each infinitesimal shift, held by the hand, paraded past words and actions that demonstrate each small movement of mind.

(For book listeners out there – narrative options exist on Audible for Great Expectations, but Simon Vance is always my top choice.)

In the opening scenes when we’re introduced to the community that surrounds young Pip, he’s cautioned to stay humble. In context, it’s a caution that can be brushed off; he has no expectations, yet.

But then Pip meets Estella.

Dickens is relentlessly repetitive, and (in this case, at least) not just because he was being paid by the word. He uses diction, the simple repetition of choice words, to drive the nail of Pip’s changing self-perception.

Pip’s mind ruminates on Estrella’s complaints: his misuse of “jacks” for “knaves” in playing cards, his “coarse hands” and “thick boots”. He perseverates on the ideas, framed by the same words while still with Estella.

Pip then cries while watched by Estella, triumphant in her dismal efficacy. He stops crying. He starts again when finally alone. Doesn’t cry when taunted a final time, but wants to.

The words are repeated yet again upon reflection on Pip’s walk home, as Dickens reminds his readers that Pip’s change in identity is holding fast.

Pip looks at his coarse hands, his thick boots. He feels shame. He becomes angry at his beloved Joe for teaching him wrongly that knaves were jacks. Pip repeats the same words – coarse hands, thick boots – his new identity markers, again and again.

Poof.

It’s moments like this that, as a writer, stealing and study overlap, and plagiarism becomes homage.

Or formula, if you prefer.